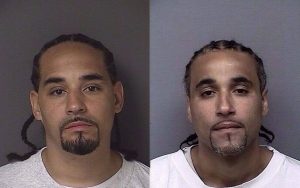

Kansas City man exonerated after 17 years of prison

After serving 17 years in prison, Richard Jones was exonerated in June of this year. With his help, the Midwest Innocence Project was able to identify the true perpetrator of the crime he was accused of, and he was cleared of the charges.

“I’m just happy to be home,” said Jones.

Jones was convicted of aggravated robbery – the allegation was purse snatching – and sentenced to 19 years in prison in 1999. Despite having a verified alibi, he was found guilty based on eyewitness identification, which the Midwest Innocence Project showed to be misidentification.

After a long night at the Moth Radio Hour on Nov. 17, hearing other people tell their stories and making plans to tell his own, Jones spent a quiet Sunday morning in his home in Kansas City. He welcomes those interested in his story and is even more pleased when it moves them to action.

“I can’t change a thing, but I can be a voice to help make that change,” said Jones. “The more voices we have, the louder we are. Someone has to hear us.”

Jones is interested in seeing the police change the “day-to-day” ways they handle investigations.

“If they have to change they will but if they don’t, they won’t,” he said.

Jones makes a point of clarifying that his desire for reform is not based in personal feelings of vindictiveness.

“A lot of people don’t understand why I’m not going for something out of this,” he said. “My compensation would be this not happening to anyone else. I don’t worry about certain things anymore like I used to. Instead of being part of the problem, I want to be part of the solution.”

Part of that solution is reform. According to the Midwest Innocence Project, which investigates possible wrongful convictions like Jones’ and others, eyewitness misidentification plays a role in more than 75 percent of wrongful convictions. Across five states, the MIP pushes for reform measures to combat misidentification. These efforts are made in addition to reviewing cases like Jones’ or that of the still incarcerated Ricky Kidd.

“Right now, we have the platform. You have to put the pieces together. They’re doing it for the right reasons. That’s how you know it’s not a job to them,” said Jones, advocating for the MIP.

In Jones’ case, he says the testimony of his alibi witnesses was deemed to be a lie and the photo lineup used to identify him was not found to be suggestive. The detectives also left a card in the front door of the house that, 17 years later, would complete their case against the true perpetrator. In spite of this, Jones doesn’t harbor resentment.

“I look at the possibilities,” said Jones. “You have to create them. They’re not always in your face.”

But his story is not completely unique. Jones was also incarcerated with two other men who were exonerated by the MIP this year. For those lacking empathy for Jones’ story and those like him, he insists hat reform is still important.

“That was three criminals on the street that shouldn’t have been,” he said.

Jones’ doppelganger, Ricky Amos, committed at least four violent felonies while Jones was incarcerated. Put another way, for every wrongful conviction, a criminal remains at large. Since the MIP and programs like it are staffed by volunteers and funded by donations, successes can be rare.

“I don’t think people should look at us, at exonerees, and feel sorry for us. Look at us as an example and hold others accountable,” said Jones.

When faced with the task of reforming an entrenched legal system, Jones draws hope from his own story. When he was denied early parole in 2015 due to behavioral issues, he said he realized negativity and anger had no place in his life anymore.

“If I plan on getting out and leading a productive life it has to start now. It can’t start when I get out,” he recalled telling himself.

“No shortcuts; I’m used to the long way. I cannot go backwards. My focus is on change. I can’t change the world, but if I can change myself, maybe I can change Kansas,” he said.

Jones said he accepts he will never get back the last 17 years of his life. He is thankful, however, for the degree of focus afforded him by not having the option of turning back.

“I lost a lot, but I gained a lot more,” he said.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Park University. Your contribution will allow us to cover our annual website hosting costs, freeing up other funds for equipment, printing and training.